The Alphabetic Principle Puzzle: Choosing a Sequence for Alphabet Instruction in Early Childhood

Recently, a school district asked me to advise them on choosing the most effective sequence of letter instruction for their early childhood program. They had a preference, based on prior use, but wanted to make sure they were making the best choice for their littlest learners. Their query led me to a very interesting analysis of popular literacy programs and their suggested alphabet instruction sequences. I began my search with their preferred program, which differed significantly from a program I had used in the classroom. The significant differences led me to expand my search, and expand and expand until I had enough evidence to categorize the sequences based on intention.

Research Base

Without a doubt, we know that emergent literacy skills lead to academic success. Learners who master the sounds (phonemes) and letters (graphemes) that comprise the English alphabet will become greater readers and spellers. (Treiman, 2005) When we teach students that letters represent sounds, we are using the alphabetic principle. We also know that instruction and practice in forming letters leads to increased letter recognition, due to the visual-motor coordination in the brain. (Zemlock, Vinci-Booher, and James 2018) Handwriting instruction and practice in preschool supports language, literacy, motor development, and emotional and behavioral self-regulation. (Gerde, 2014) Furthermore, the research of Graham et al. (2000), supports the idea that the cognitive load of a child is lifted when their handwriting is fluent and accurate. This is compounded with the evidence that early writing skill predicts later academic achievement. (Dinehart and Manfra, 2013) We also know, from a Guo et al. study in 2018, that preschool children’s ability to write upper and lower-case letters was significantly related to letter-sound knowledge. Effective instruction in letter-sound knowledge necessitates students identifying sounds, naming letters, and associating the letters to sounds. (Foorman et al. 2016)

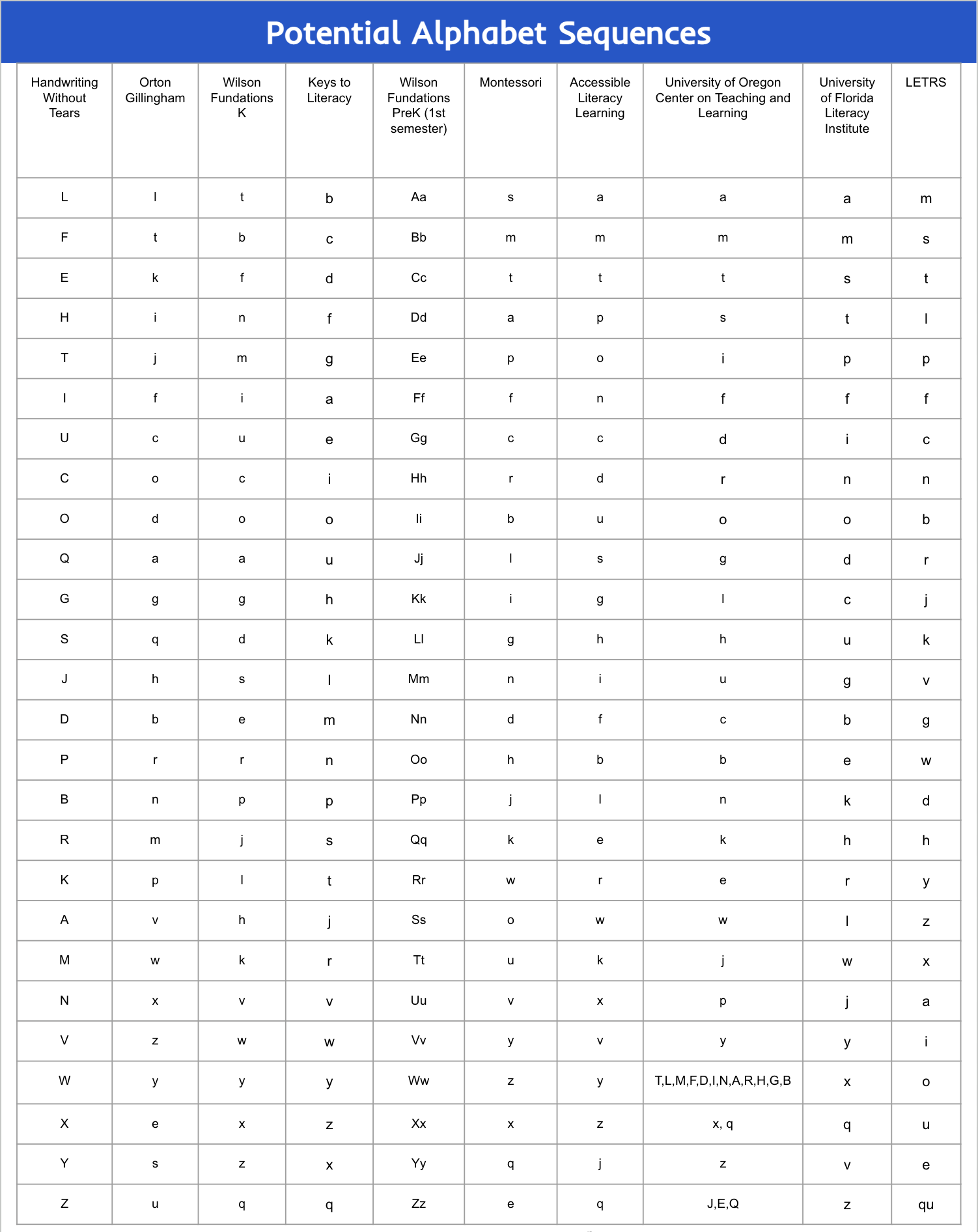

Program Analysis

Using the understanding of the necessary components of early childhood literacy indicated above, consider the programs I examined for their instructional alphabetic sequence in PreK or K.

At first glance, you’ll notice some significant similarities and differences, specifically in approach to letter formation, lower-case and upper-case letters, and approach to letter/sound correspondance. Below, I’ll break down the theories or research that support each program’s choice and intent. The links on each program title will take you to the scope and sequence or research base that I was able to find. Note that I was specifically looking for a rationale for the sequence of alphabet instruction for PreK and K learners.

Handwriting without Tears:

The order of letters is instructed in groups of stroke types. Stroke types include vertical & horizontal, magic c, big and little curves, and diagonals. According to the scope and sequence, capital letters are easier for students to recognize and write, which is why they are taught first. The guidance does not include a preference for teaching letter sounds or names first.

Orton Gillingham:

Orton Gillingham separates letter instruction into two groups: foundational and corrective. For foundational letters, explicit letter formation instruction should occur at the same time as instruction on letter names and sounds. Instruction should separate letters that are visually similar and those with similar sounds. For both foundational and corrective, the order of letters is done by type of stroke: discontinuous, donut, pull down, diagonal, and special. For corrective instruction, start with lowercase, then capitals because lowercase make up more than 97% of written text.

Wilson Fundations K:

In similar fashion as Handwriting without Tears and Orton Gillingham, letter instruction is grouped by similar formations. Wilson teaches lowercase formation first. Students learn to recognize and name letters, learn their formation, and learn their sound, simultaneously.

Wilson Fundations PreK:

For this study, I analyzed their first semester sequence, which is presented in alphabetical order for letter-sound correspondence of both upper and lower-case letters. According to their manual, letter formation instruction for lowercase and uppercase letters comes in the 2nd semester.

Montessori:

In the Montessori approach, lower-case letters are introduced via sound first. Letter names come after the sound is mastered. The goal is to make words with the letters learned. A coda of this instructional approach is that the first letter of a child’s name can be introduced early on in the sequence. The guidance for letter formation is exploratory and sensory, and makes use of sand trays and other tactile manipulatives.

Accessible Literacy Learning:

This program, which was researched out of Penn State, insists on first teaching lower-case letters and letters that occur frequently in simple words, so students can begin to read. Letters that look and sound similar are separated in instruction, which starts by teaching the sounds of letters, not names. This guidance does not make reference to instruction in letter formation.

Keys to Literacy:

Researcher Joan Sedita advises that letter instruction is ordered from most basic sound to most complex sound. She starts with consonants, adding that vowels can be introduced after some consonants. The intent here is that once students know a few consonants and vowels, they can begin to read and spell words. This guidance does not make reference to instruction in letter formation.

University of Oregon’s Center for Teaching and Learning:

This guidance says to introduce lower case letters first and teach sounds that can be used to build words; in addition, they advise separating visually similar letters. They explicitly advise teaching recognition of some upper-case letters before finishing instruction in the entire lower-case alphabet. The guidance does not make reference to instruction in letter formation.

University of Florida Literacy Institute:

The guidance from this body of research advises introducing letter names, sounds, and formation simultaneously, but does not provide a rationale for the order of the letters in their scope and sequence. There is no reference to instruction in letter formation.

LETRS:

This sequence, created by Louisa Moats and Carol Tolman, advises the introduction of predictable consonants, then predictable short vowels. It does not make reference to instruction in letter formation.

Quite a Puzzle

Consider the options above: it’s clear that some are heavier on letter-sound correspondence, while others are heavier on letter formation. One thing became clear: the intent of the program is clearly evident in its scope and sequence. My own bias had me initially leaning towards the sequences that start with easily buildable and blendable letters, such as a, m, s, t, p. In my experience, my learners were able to encode and decode simple CVC words early into the school year; more letters learned equated to more words built and read. I also know, however, that my intent for those learners was decoding and encoding- I was not so concerned with their letter formation skills.

Conclusion

After carefully considering the proposed sequences and the client in question, I believe that choosing “the most effective sequence” comes with the necessity to understand the outcomes you are searching for. What will effective look like for your students? Is it the ability to connect letters to sounds to read and spell simple words? Or is it developing the fine motor skills necessary to write? After several days of research and analysis, I do not have a concrete answer for my client; instead, I have guiding questions that I can use to better understand their students’ needs, and the intentions for learning outcomes. Only then will I be able to recommend a program for its anticipated effectiveness.

Resources for Further Understanding

Indiana Alphabet Knowledge and Handwriting

Handwriting in early childhood (Zaner Bloser)

References

Dinehart LHB and Manfra L (2013) Association between early fine motor development and later math and reading achievement in early elementary school. Early Education and Development 24(2): 138–161.

Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J., Hayes, L., Henke, J., Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from the NCEE website: http://whatworks.ed.gov.Gerde, H. K. (2014, August). Writing in early childhood classrooms: Guidelines for best practices. Columbus, OH.Graham S, Harris KR and Fink B (2000) Is handwriting causally related to learning to write? Journal of Educational Psychology 92(4): 620–633.

Guo, Y., Breit-Smith, A., Hall, A. H., & Biales, C. (2018). Exploring preschool-age children's ability to write letters. Journal of Research in Education, 28(2), 35–51.

Treiman, R. (2005). Knowledge about letters as a foundation for reading and spelling. In R. M. Joshi & P. G. Aaron (Eds.), Handbook of orthography and literacy (pp. 581-600). Routledge.

Zemlock, D., Vinci-Booher, S. & James, K.H. Visual–motor symbol production facilitates letter recognition in young children. Read Writ 31, 1255–1271 (2018).